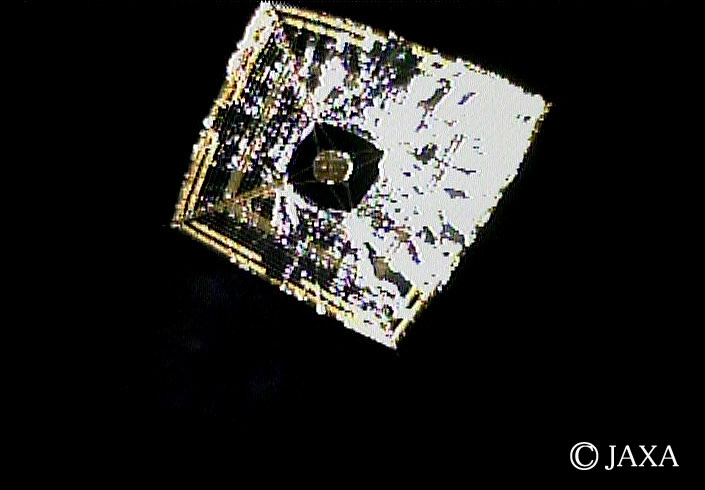

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania have developed a novel technique for controlling solar sails, potentially transforming how these vessels navigate in space. In a pre-print paper, authors Gulzhan Aldan and Igor Bargatin introduce a method that employs kirigami, an ancient Japanese paper-cutting art, to adjust the sail’s angle and enhance its propulsion capabilities without the reliance on traditional propellants.

Revolutionizing Solar Sail Mechanics

Solar sails harness sunlight for propulsion, offering significant advantages over conventional methods, primarily by eliminating the need for propellant. However, steering these sails presents a challenge. Traditional sailing relies on a captain adjusting the angle of the sail, aided by a rudder. In contrast, solar sails lack this rudder functionality, complicating their maneuverability.

The new kirigami approach addresses this issue by creating specific cuts in the sail material, allowing it to mechanically buckle. This buckling alters the angle at which light reflects off the sail, enabling more precise navigation. Each unit cell of the sail is designed with cuts running in different directions on a standard material known as aluminized polyimide film.

When tension is applied to the film, the cuts facilitate a 3D transformation, tilting sections of the sail in relation to the light source. This enables each buckled segment to act like a tiny mirror, reflecting light at varying angles and generating thrust in the opposite direction. This innovative method not only simplifies the turning process but also reduces reliance on heavy components.

Comparative Advantages of the Kirigami Sail

Current methods for steering solar sails include reaction wheels, tip vanes, and Reflectivity Control Devices (RCDs). Reaction wheels, commonly used in satellites, are heavy and consume propellant. Tip vanes, which are small, rotatable mirrors, pose mechanical complexities and are prone to failure. RCDs, while effective in adjusting reflectivity, require continuous power, draining batteries even when not in use.

In contrast, the kirigami sail’s design primarily relies on servo motors, which are known for their power efficiency and only consume energy during operation. This feature distinguishes the kirigami technique as a more sustainable and lightweight solution.

The authors validated their method through simulations and physical experiments. Using the COMSOL physics simulation package, they conducted ray tracing experiments to measure the forces acting on the sail at various angles of buckling. Although the forces measured were small—1 nanonewton per watt of sunlight—the cumulative effect is sufficient to maneuver a small solar sail and its payload over time.

In practical tests, the researchers created a prototype by cutting film and placing it in a test chamber where a laser was directed onto it. They then applied tension to the film, observing the laser’s movement across the chamber wall. The results aligned closely with their predictions, demonstrating the effectiveness of the kirigami design.

While the potential for this technology to influence the future of solar sailing is significant, challenges remain. Competing technologies also aim to enhance maneuverability, and limited experimental missions hinder comprehensive testing of these innovations. Consequently, it may take time before the kirigami sail is deployed in space.

Nevertheless, when this technology is eventually realized, the visual impact of a kirigami solar sail in action could be remarkable, marking a significant step forward in space exploration methodologies.

For further reading, refer to the work of G. Aldan and I. Bargatin on low-power solar sail control using in-plane forces from tunable buckling of kirigami films.