Research conducted by a team at New York University has revealed groundbreaking insights into prehistoric ecosystems by analyzing thousands of preserved metabolic molecules in fossilized bones. These findings, published in the journal Nature, offer a new understanding of ancient animals’ diets, health, and the climates they inhabited, which were significantly warmer and wetter than today.

For the first time, scientists successfully examined metabolites in bones dating back 1.3 to 3 million years. This innovative approach allows researchers to reconstruct not only the biology of these ancient creatures but also the environmental conditions they experienced. By focusing on metabolic signals that relate to health and nutrition, the team gained insights into climatic factors, including temperature, soil quality, and rainfall.

Timothy Bromage, a professor of molecular pathobiology at NYU and leader of the research team, expressed his enthusiasm for applying metabolomics to fossils. He stated, “It turns out that bone, including fossilized bone, is filled with metabolites.” This discovery stems from previous research indicating that collagen, a vital protein in bones, can survive in ancient specimens. Bromage hypothesized that metabolites, which circulate in the blood, could also be trapped within bone structures.

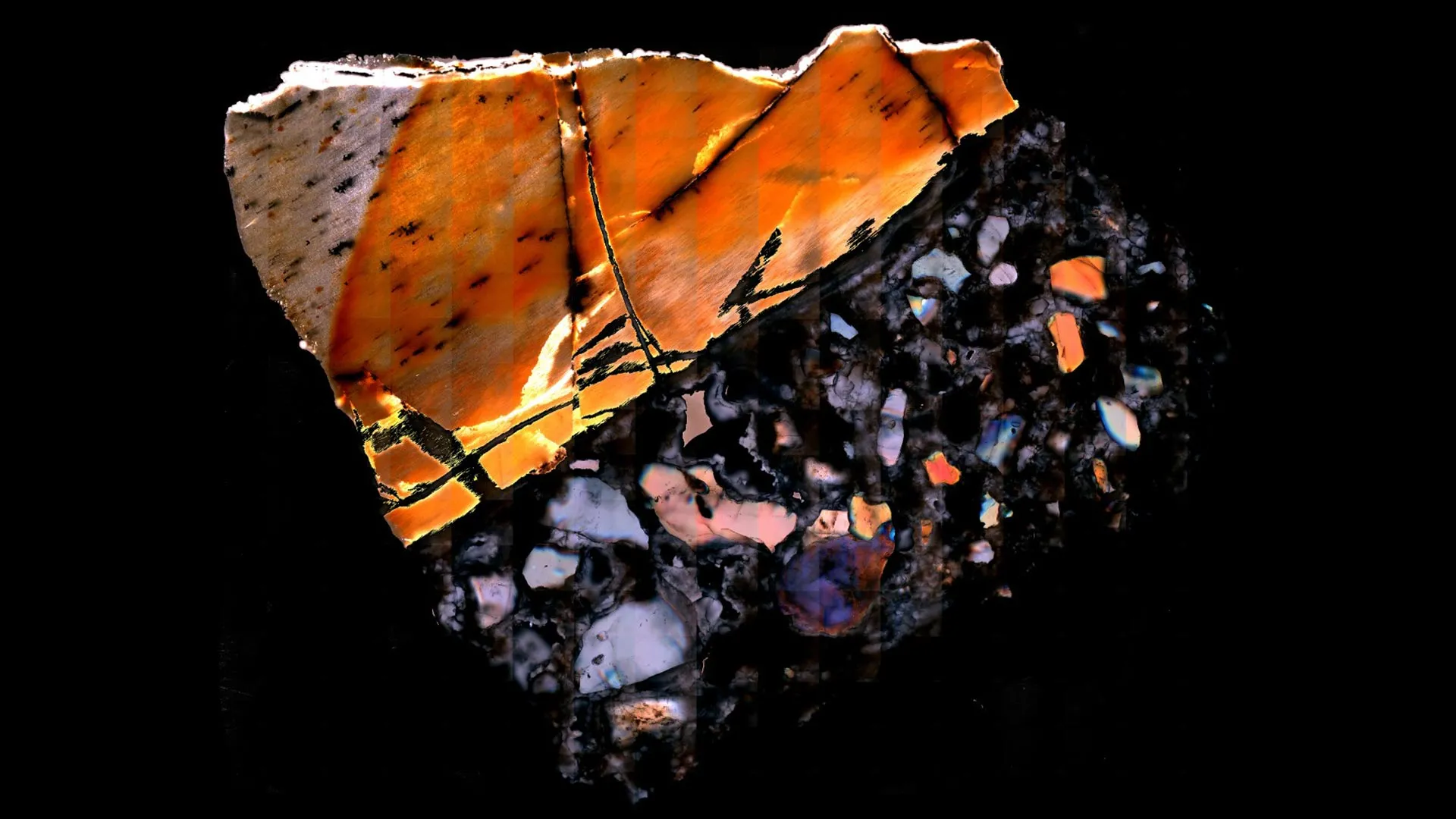

The research team employed mass spectrometry, a technique that identifies molecules by converting them into charged particles, to identify nearly 2,200 metabolites in modern mouse bones. This method was then applied to fossilized bones excavated from regions in Tanzania, Malawi, and South Africa, which are notable for early human activity. The fossils studied included a variety of species, from rodents to larger mammals like an antelope and an elephant.

Many of the metabolites discovered mirror those found in contemporary species, providing a glimpse into the biology of these ancient animals. For instance, some metabolites indicated the presence of estrogen-related genes, suggesting that certain fossilized animals were female. In one significant case, a ground squirrel bone from Olduvai Gorge, dated to approximately 1.8 million years ago, showed signs of infection by the parasite responsible for sleeping sickness in humans, Trypanosoma brucei. Bromage noted, “We discovered in the bone of the squirrel a metabolite unique to the biology of that parasite.”

The research also shed light on the diets of these ancient animals. Although databases for plant metabolites are less comprehensive than those for animals, the team identified compounds linked to local flora, including aloe and asparagus. Bromage explained, “What that means is that, in the case of the squirrel, it nibbled on aloe and took those metabolites into its own bloodstream.” This information allows for a better understanding of the environmental conditions in which these animals lived, including temperature and rainfall patterns.

The reconstructed habitats align with previous geological and ecological studies. For example, the Olduvai Gorge Bed has been described as a freshwater woodland and grassland environment, while other areas indicate drier woodlands and marshy conditions. Across all studied locations, the fossil evidence consistently points to climates that were wetter and warmer than those observed today.

The research team, which included scientists from various institutions across France, Germany, Canada, and the United States, received support from The Leakey Foundation and additional funding for scanning electron microscopy from the National Institutes of Health.

Bromage concluded that utilizing metabolic analyses to study fossils could revolutionize our understanding of ancient environments, enabling researchers to reconstruct prehistoric ecosystems with unprecedented detail. This innovative approach marks a significant step forward in paleobiological research, opening new avenues for exploring the complex interplay between ancient organisms and their habitats.