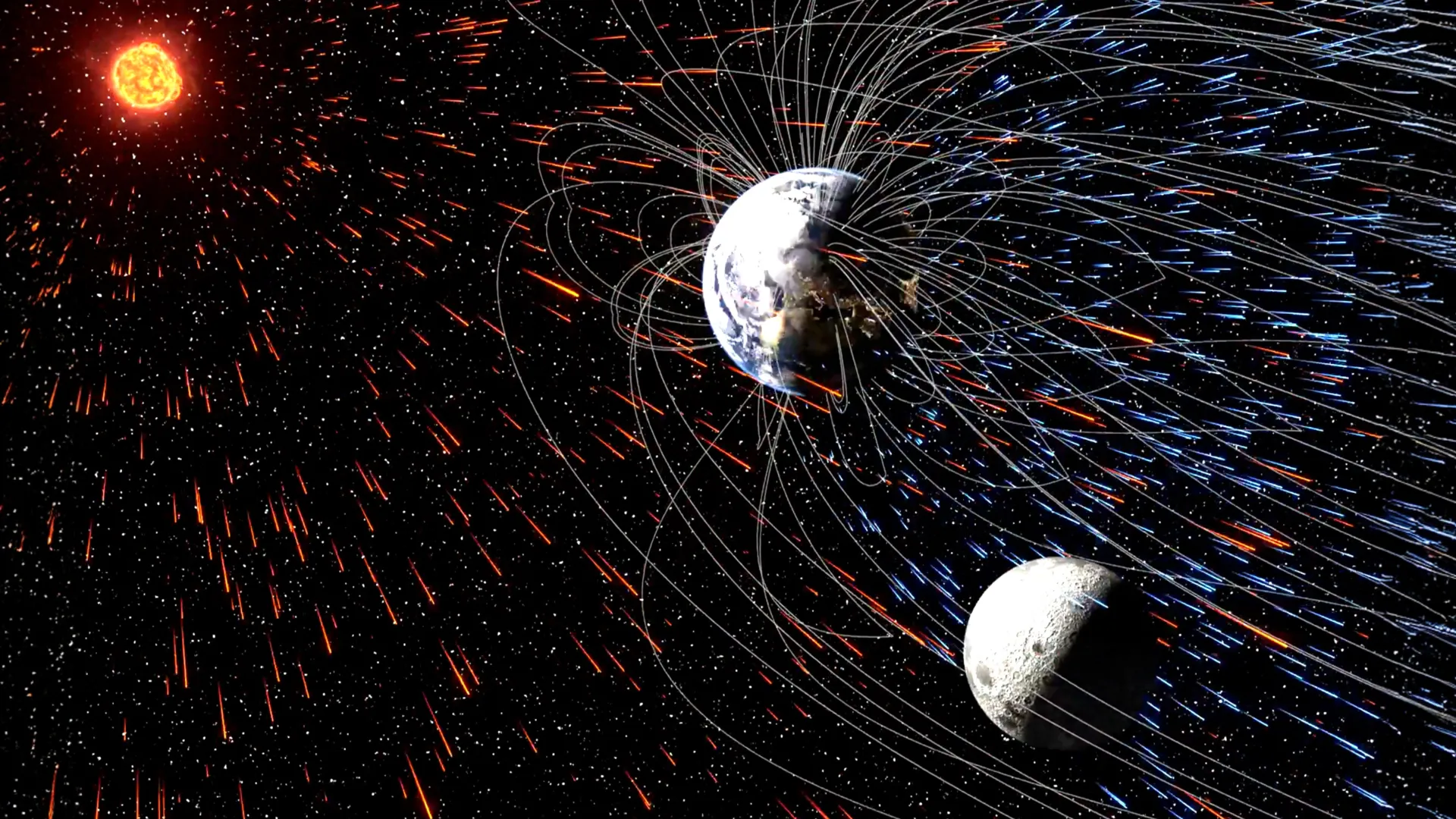

Earth has been transferring tiny particles from its atmosphere to the moon for billions of years, according to new research from the University of Rochester. This phenomenon, influenced by Earth’s magnetic field, has been revealed as a significant factor in the movement of atmospheric materials across vast distances, potentially explaining the presence of certain gases found in lunar samples.

While the moon appears barren and lifeless, the findings suggest that its surface may actually record a complex history of Earth’s atmosphere. The study, published in Nature Communications Earth and Environment, indicates that atmospheric particles, propelled by the solar wind, can travel along Earth’s magnetic field lines to reach the moon. This process may not only document Earth’s atmospheric history but could also present valuable resources for future lunar exploration.

Eric Blackman, a professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Rochester, explains, “By combining data from particles preserved in lunar soil with computational modeling of how solar wind interacts with Earth’s atmosphere, we can trace the history of Earth’s atmosphere and its magnetic field.” This research opens up the possibility that lunar soil acts as a long-term archive of our planet’s atmospheric changes.

Understanding the Transfer of Atmospheric Particles

Researchers have long pondered the mechanisms through which the moon acquires material from Earth. Previous analyses of moon rocks and soil collected during the Apollo missions revealed that the lunar regolith contains volatile substances, including water, carbon dioxide, and nitrogen. While some of these materials are known to originate from the solar wind, the quantities, especially nitrogen, exceed what solar wind alone could provide.

In 2005, scientists from the University of Tokyo suggested that a portion of these volatiles came from Earth’s atmosphere, proposing that this transfer only occurred before the establishment of a significant magnetic field. They believed that once the magnetic field formed, it would block atmospheric particles from escaping into space.

In contrast, the Rochester team conducted advanced computer simulations to explore this issue further. The research team, which included graduate student Shubhonkar Paramanick and professor John Tarduno, modeled two scenarios: one without a magnetic field and another reflecting the current state of Earth with a strong magnetic field.

The simulations demonstrated that particle transfer to the moon was significantly more efficient under present-day conditions, where Earth’s magnetic field actively guides charged particles from the upper atmosphere. Over billions of years, this mechanism has created a steady flow of atmospheric materials reaching the lunar surface.

Implications for Future Lunar Exploration

The implications of this research extend beyond understanding Earth’s atmospheric history. The presence of volatile elements in lunar soil suggests that the moon may harbor resources beneficial for sustaining human activity in the future. Water and nitrogen, for instance, could reduce the need for transporting supplies from Earth, making long-term lunar habitation more feasible.

“Our study may also have broader implications for understanding early atmospheric escape on planets like Mars,” Paramanick adds. “By examining planetary evolution alongside atmospheric escape across different epochs, we can gain insight into how these processes shape planetary habitability.”

Supported by funding from NASA and the National Science Foundation, this research not only sheds light on the moon’s geological history but also emphasizes the potential for sustainable human presence on the lunar surface. As scientists continue to study lunar soil, they may uncover new insights that enhance our understanding of both Earth and its celestial neighbor.