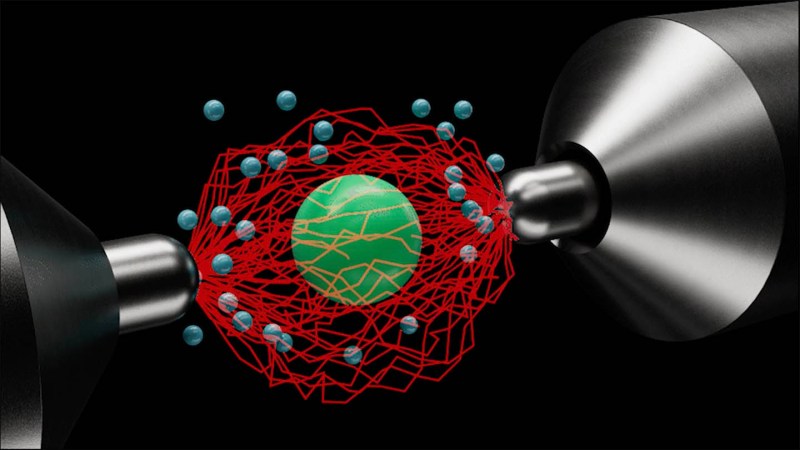

A groundbreaking study from the University of Hawaii at Mānoa reveals that waste from deep-sea mining operations poses a significant threat to marine ecosystems in the Pacific’s biodiverse Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ). Published in Nature Communications, this research is the first to demonstrate the potential disruption of midwater food webs in the ocean’s “twilight zone,” a region crucial for sustaining various marine species.

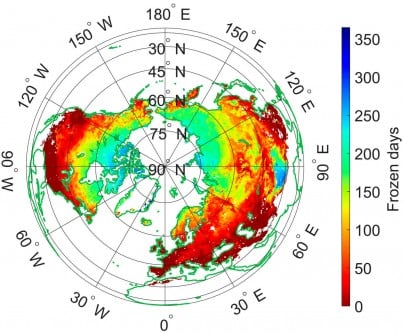

The study indicates that approximately 53% of all zooplankton and 60% of micronekton—creatures that feed on zooplankton—could be adversely affected by the discharge of mining waste. This contamination risks altering the food web, ultimately impacting larger predators that rely on these organisms for sustenance.

Impact of Deep-Sea Mining on Marine Life

Michael Dowd, the lead author and a graduate student at the University of Hawaii, describes the consequences of mining waste entering the ocean. He compares it to creating water as cloudy as the muddy Mississippi River, which hinders the natural food sources for tiny, drifting zooplankton. This disruption could have cascading effects throughout the food chain, as micronekton—small shrimp, fish, and other animals that rely on zooplankton—are also affected.

The research, titled “Deep-sea mining discharge can disrupt midwater food webs,” examines the impact of waste released during a mining trial in 2022 within the CCZ. This area of the Pacific Ocean is targeted for the extraction of polymetallic nodules containing essential minerals such as cobalt, nickel, and copper. Researchers analyzed water samples from depths impacted by mining activities, revealing that the mining waste contained significantly lower concentrations of amino acids—a vital indicator of nutritional value—compared to naturally occurring particles that support life in these depths.

Co-author Erica Goetze, a professor in the School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST), emphasizes the broader implications of the findings. “This isn’t just about mining the seafloor; it’s about reducing the food for entire communities in the deep sea,” she stated. The study underscores the importance of understanding the ecological consequences of mining before it escalates to a commercial scale.

Regulatory Challenges Ahead

As demand for metals used in electric vehicle batteries and other low-carbon technologies increases, some countries are intensifying their efforts in deep-sea mining. Currently, around 1.5 million square kilometers of the CCZ are licensed for such activities. This raises urgent concerns about the potential long-lasting impacts on marine ecosystems if appropriate environmental safeguards are not established.

Deep-sea mining involves collecting nodules from the ocean floor, along with seawater and sediment, which are then transported and separated at a collection ship. The sediment waste, mixed with seawater, must be returned to the ocean. Though the specific discharge depth remains unclear, some mining operators have suggested releasing it within the twilight zone. Until now, the effects of such discharges on midwater communities were not well understood.

“Mining plumes don’t just create cloudy water—they change the quality of what’s available to eat, especially for animals that can’t easily swim away,” said Jeffrey Drazen, another co-author and a professor of oceanography. He likened the situation to introducing “empty calories” into an ecosystem that has evolved to thrive on a balanced diet over centuries.

The study’s authors call for enhanced research and regulatory frameworks to protect these crucial ecosystems. They advocate for careful consideration of the depth at which mining waste is discharged, as its impact can vary significantly based on location. “Improper discharge could cause harm to communities from the surface to the seafloor,” Drazen added.

As commercial deep-sea mining has yet to begin on a large scale, the researchers emphasize the importance of making informed decisions now. Brian Popp, co-author and an earth sciences professor at SOEST, warns that failing to understand the potential risks could lead to irreversible damage to ecosystems that are only beginning to be explored.

The findings aim to inform regulatory actions by international authorities, including the International Seabed Authority and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which oversees environmental assessments of U.S.-led deep-sea mining projects.

This study highlights the necessity for comprehensive research to protect the full vertical extent of ocean ecosystems, ensuring that marine life continues to thrive in a world increasingly reliant on deep-sea resources.