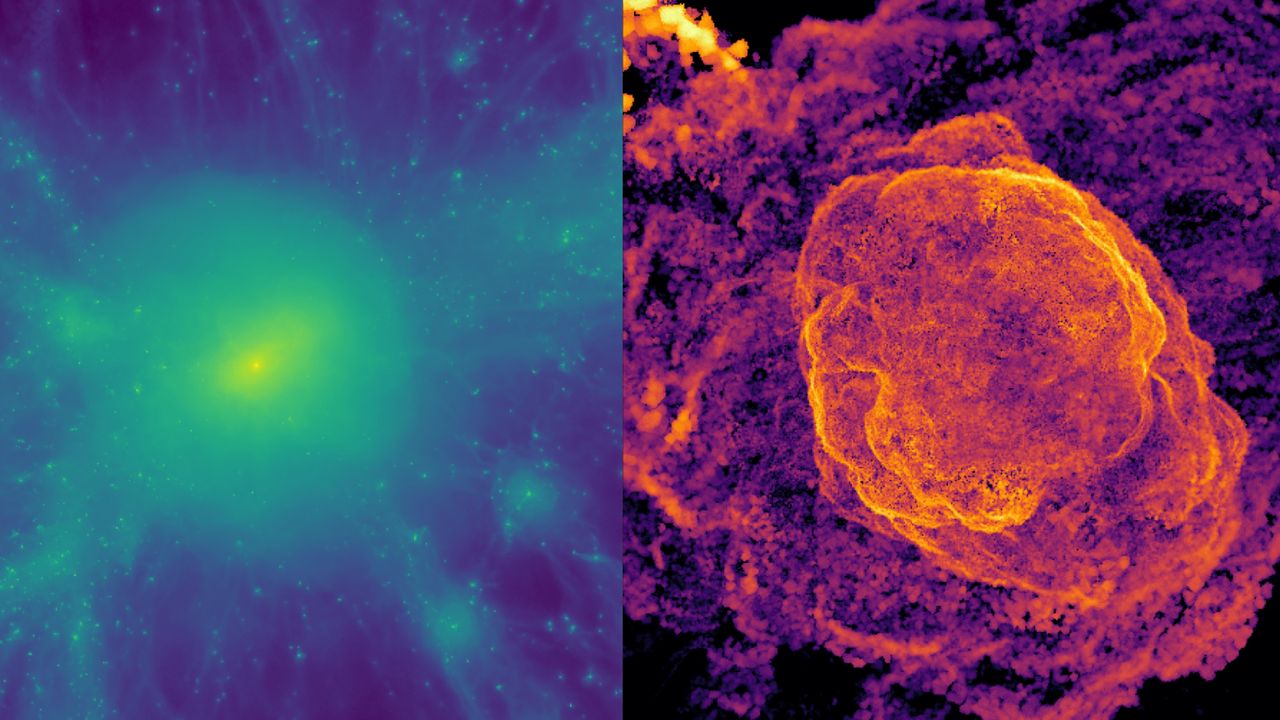

A team of researchers from the Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam (AIP) has made significant strides in understanding the enigmatic structures known as “radio relics,” which are formed during the colossal collisions of galaxy clusters. These ghostly radio emissions, stretching across millions of light-years, have puzzled astronomers for years. The team’s findings, published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics on November 18, 2023, shed light on the physics behind these phenomena and offer a clearer picture of their formation and behavior.

Understanding the Formation of Radio Relics

Radio relics are created by shock waves that accelerate electrons to nearly the speed of light. Despite cataloging numerous such structures, their underlying physics remained elusive. Observations from prominent telescopes, including NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and Europe’s XMM-Newton, indicated that the magnetic fields within these relics are much stronger than existing models predicted. Additionally, discrepancies between radio and X-ray measurements of shock strengths have long perplexed scientists.

To tackle these challenges, the research team, led by postdoctoral researcher Joseph Whittingham, employed high-resolution simulations to trace the evolution of radio relics. They focused on a particularly energetic merger between two galaxy clusters, one approximately 2.5 times heavier than the other. As these clusters merged, they unleashed enormous shock waves that spanned nearly 7 million light-years.

Revealing the Physics Behind Radio Emissions

Utilizing data from their simulations, the researchers created detailed “shock-tube” models to analyze the intricate physics occurring at the shock front. This multi-scale approach allowed them to explore how electrons are accelerated at these shock fronts and how the resultant radio emissions are perceived by telescopes. The simulations revealed that when shock waves interact with cold gas falling into a galaxy cluster, they compress plasma into dense sheets. This interaction amplifies magnetic field strengths well beyond expectations, aligning with observed data.

“The whole mechanism generates turbulence, twisting and compressing the magnetic field up to the observed strengths, thereby solving the first puzzle,” said Christoph Pfrommer, a co-author of the study.

The study also clarified that as shock waves sweep through dense gas clumps, certain regions of the shock front accelerate electrons more efficiently, producing bright patches that dominate radio emissions. In contrast, X-ray telescopes measure the average strength of shocks, including weaker areas, which explains the long-standing discrepancies in observations.

Ultimately, the simulations demonstrate that only the strongest parts of the shock front contribute significantly to the radio emissions, validating the core physics of radio relics despite the lower average strengths suggested by X-ray data. This comprehensive understanding resolves several persistent questions about these cosmic structures.

The success of this research motivates the team to further explore unresolved mysteries related to radio relics. Whittingham stated, “This success motivates us to build on our study to answer the remaining unresolved mysteries surrounding radio relics.” These findings mark a notable advancement in astrophysics, enhancing our comprehension of the complex processes that govern the universe.