Researchers have made a significant advancement in understanding how the influenza virus invades human cells. A collaborative study between scientists from Switzerland and Japan has led to the development of a novel imaging technique, allowing for real-time observation of the virus’s entry into cells.

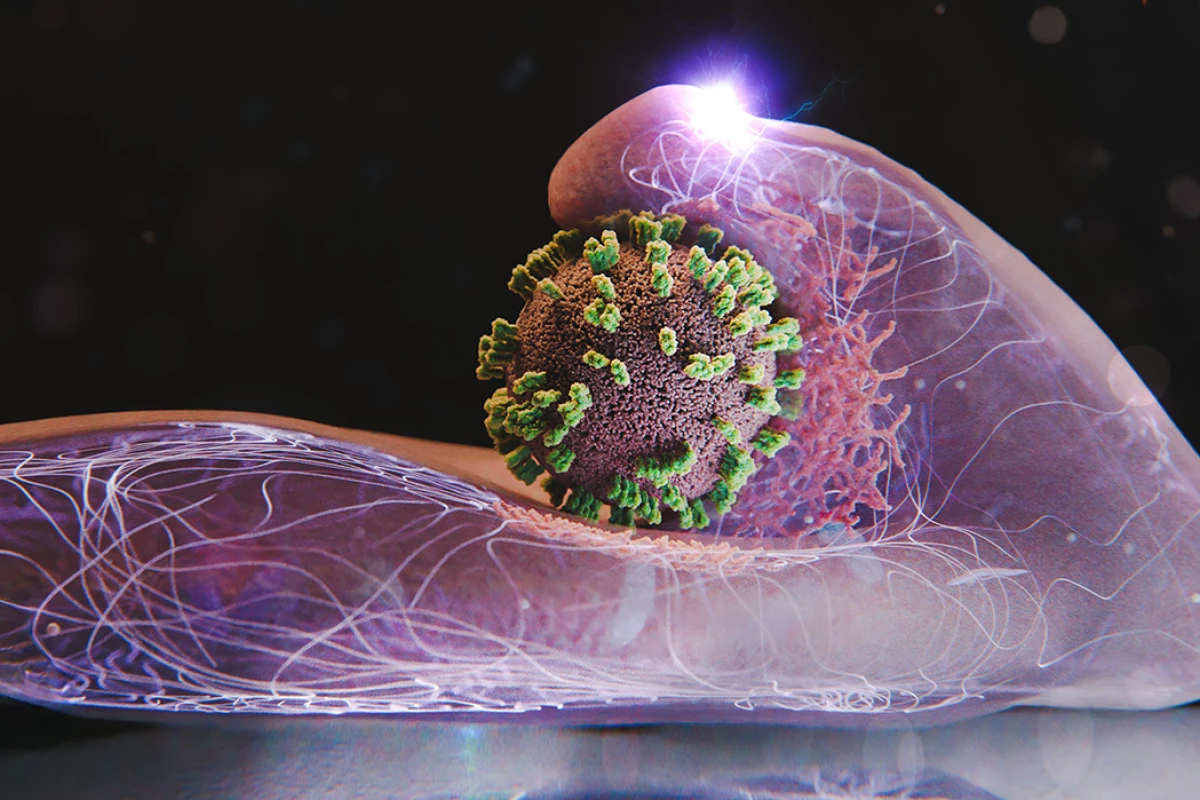

The influenza virus, notorious for its seasonal outbreaks, utilizes two key proteins, hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA), to infiltrate host cells. These proteins attach to sialic acids on the cell’s surface, facilitating the virus’s entry through a process known as endocytosis. Traditionally, capturing the virus’s rapid movements during this invasion has posed a challenge, as conventional microscopes lack the necessary resolution.

In a groundbreaking study published in the journal PNAS, researchers introduced a hybrid imaging system called virus-view dual confocal and AFM (ViViD-AFM). This innovative tool combines atomic force microscopy (AFM) with fluorescence microscopy, enabling scientists to observe living human cells with unprecedented detail.

Yohei Yamauchi, a researcher at ETH Zurich, noted that the new system revealed an unexpected dynamic in the interaction between the virus and the host cell. Contrary to previous assumptions that cells passively accept viral intrusion, the study found that the cells actively respond, stretching and attempting to engage with the virus. Yamauchi described this interaction as a “dance between virus and cell.”

The team utilized their advanced imaging system to examine how individual influenza particles navigate the cell surface under various conditions. They manipulated viral proteins, limited binding sites, and experimented with different virus types to observe the effects on the entry process. The findings indicated that flu viruses require larger bulges on the cell’s surface, created by the protein actin, to facilitate entry. Remarkably, these bulges were unaffected by certain inhibitors, suggesting a resemblance to other cellular activities.

Once a virus attaches to receptor clusters on a cell, it triggers signals that prompt the cell to envelop the virus in a clathrin coat, forming an actin bulge that pulls the virus inward. Ultimately, the virus is encapsulated into a vesicle, which transports it deeper into the cell toward the nucleus.

The implications of the ViViD-AFM technique extend beyond understanding influenza. Researchers anticipate using this tool to evaluate the effectiveness of antiviral drugs in real time within living cells. Additionally, the method could be adapted to study the behavior of other viruses and the interaction of vaccines with cells.

This advanced microscopy approach presents a new avenue for biological research, offering insights into how viruses attach and enter cells. It could also aid in the study of how cells release extracellular vesicles and how nanoparticles designed for drug delivery penetrate cell membranes.

In conclusion, the ViViD-AFM technique not only enhances our understanding of viral behavior but also opens doors for significant advancements in drug research and development. As researchers continue to explore the intricate dynamics of cell-virus interactions, this breakthrough could lead to major discoveries in biology and medicine.