Research led by astrophysicist Ryo Sawada at the Institute for Cosmic Ray Research, University of Tokyo, suggests that cosmic rays from nearby supernovae could play a pivotal role in the formation of Earth-like planets. This finding may change longstanding assumptions about how these planets, similar to Earth, develop in the universe.

For decades, scientists have theorized that the early solar system was enriched with short-lived radioactive elements, such as aluminum-26, by the explosion of a nearby supernova. These elements were crucial in shaping rocky planets by heating young planetesimals, leading to the loss of water and other volatile materials. However, this “injection” model relied on a highly unlikely scenario: the supernova had to explode at just the right distance, close enough to deliver radioactive materials without destroying the protoplanetary disk.

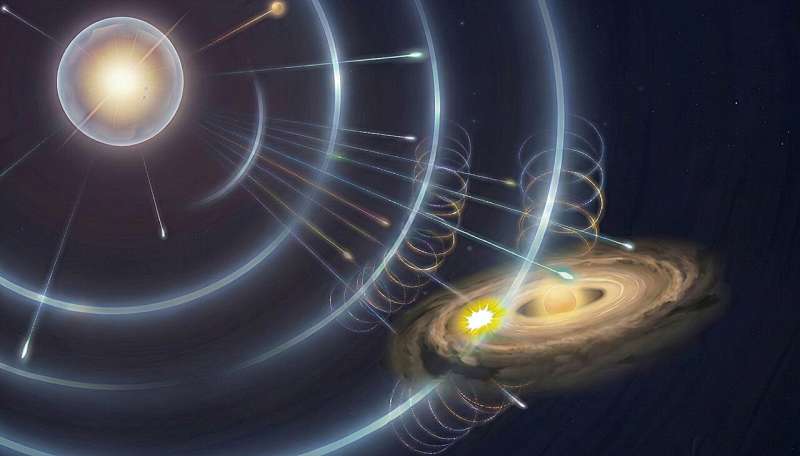

This model left a significant question unanswered—was Earth’s formation truly dependent on such a rare event? In exploring this, Ryo Sawada and his team examined an alternative perspective, emphasizing the role of supernovae not only as explosive events but also as powerful particle accelerators. Their research, published in Science Advances on December 21, 2025, introduces the idea of a “cosmic-ray bath.”

According to their simulations, when cosmic rays interact with the protosolar disk, they can initiate nuclear reactions that naturally produce important radioactive elements like aluminum-26. Surprisingly, the research indicated that these processes could occur at distances of about one parsec from a supernova—a distance commonly found in star clusters.

This shifted the understanding of planetary formation. Instead of relying on a rare injection of materials, it is now proposed that the young solar system simply needed to exist in the vicinity of massive stars that eventually went supernova. This “cosmic-ray bath” mechanism appears to be a more universal process that could be prevalent in many star-forming regions.

The implications of this research are significant. If the conditions necessary for forming water-depleted rocky planets like Earth are common, then the universe may host a larger number of Earth-like planets than previously thought.

“If cosmic-ray immersion is sufficient—and common—then the conditions that helped shape Earth may arise around a large fraction of sun-like stars,”

noted Ryo Sawada.

Despite this promising insight, the study does not imply that every supernova guarantees the presence of habitable planets. Various other factors, including the lifetime of the protoplanetary disk and the dynamics within star clusters, play crucial roles in planetary formation.

This research serves as a reminder of the interconnectedness of astrophysical processes. The findings highlight how a phenomenon typically associated with high-energy astrophysics, such as cosmic-ray acceleration, can also impact questions regarding planetary science and habitability.

In summary, the work of Ryo Sawada and his colleagues suggests that the origins of Earth-like planets may be more widespread than once believed, opening new avenues for understanding how planetary systems evolve in our universe.