The debate between science and religion continues to evoke strong opinions across various communities. John Klimenok Jr., a resident of Plainfield, offers a critical examination of this interplay, engaging with perspectives on existence, the origins of life, and the concept of an afterlife.

Klimenok references insights from Tom McKone, who argues that science fundamentally relies on evidence and objective inquiry. According to McKone, while science has made significant strides in understanding the universe, it falls short of answering profound existential questions such as the origin of life, the purpose of human existence, and the nature of a higher power. He contends that science can describe how the universe operates, but it does not provide definitive answers about the existence of God or what follows death.

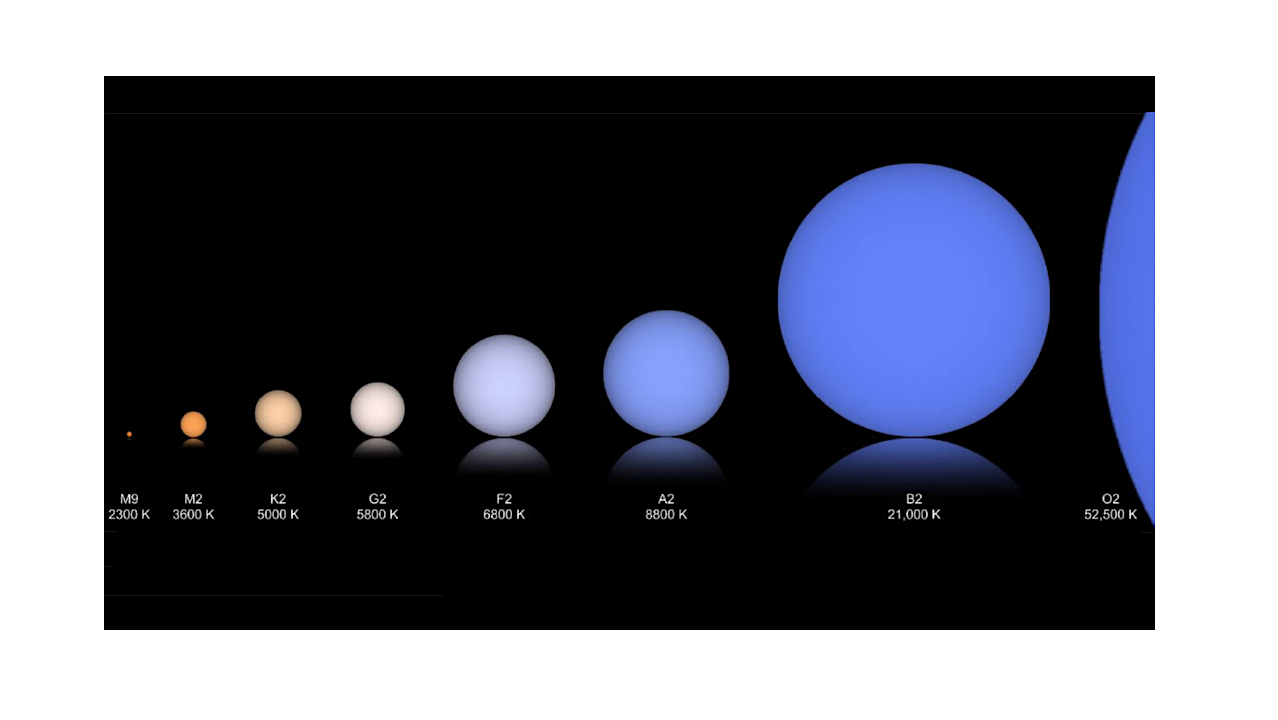

In the realm of scientific inquiry, Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity plays a pivotal role. It posits that the universe began as a singularity, an infinitesimally small point of immense energy, leading to the Big Bang approximately 13.7 billion years ago. From this event, not only light and matter emerged, but also the dimensions of space and time. Current scientific understanding suggests that the universe is infinite, with mathematical models explaining its natural formation without invoking a divine creator.

The concept of the anthropic principle is also addressed. This principle implies that the universe is finely tuned to support life as we know it, contingent upon four critical constants: the masses of the electron and proton, and the strengths of the electromagnetic and strong nuclear forces. Changes in these constants could render life, as we understand it, impossible. Klimenok notes that while this principle suggests a tailored universe, it may be more accurate to assert that humanity is adapted to the universe rather than the other way around.

Klimenok also discusses the implications of life’s timeline on Earth, emphasizing that it took around 9 billion years for the Sun and Earth to form, followed by a billion years for life to emerge, and another 4 billion years to develop humans. This timeline raises questions about the perceived inefficiency of divine creation, given that humans have existed for less than 0.01% of the Earth’s history.

In contemplating what occurs after death, Klimenok refers to neuroscientific findings that map brain functions related to cognition and sensory perception. He argues that once the brain ceases to function, the body begins to decompose, undermining the notion of an immaterial spirit surviving death. He points to the belief held by many Christians in the resurrection of Jesus Christ as a source of hope for life after death, questioning its validity based on the timelines and narratives presented in the Gospels.

The earliest Gospel, that of Mark, is believed to have been written approximately 40 years after the death of Jesus. Klimenok highlights that the original ending of this Gospel does not mention the resurrection, suggesting that later writers, such as those of Matthew and Luke, felt compelled to provide additional accounts of this event. He references Matthew 16:28 and Luke 9:27, where Jesus speaks of his return, questioning the implications of his absence even after nearly 2,000 years since his crucifixion.

Klimenok draws attention to the author of 2 Peter, who posits that “one day with the Lord is as a thousand years.” This perspective acknowledges the discrepancy between the anticipated return of Jesus and the reality of time passing without fulfillment of the prophecy. Klimenok asserts that the author of 2 Peter could not have been Peter himself, as biblical scholars recognize it as a second-century document.

Ultimately, Klimenok concludes that human existence is finite. He expresses a desire to embrace life fully, acknowledging the inevitability of his own mortality. He advocates for a life focused on the present, striving to make a positive difference during one’s time on Earth.

This exploration of the science-religion dynamic not only reflects personal beliefs but also invites broader conversations about understanding our place in the universe and the nature of existence itself.