Researchers at Space Park Leicester have created the Fluorescent Deep Space Petri-Pod (FDSPP), a cutting-edge platform for conducting biological experiments in space. This initiative, funded by the UK Space Agency and supported by Voyager Technologies, aims to investigate the effects of microgravity and radiation on the development of living organisms, addressing critical challenges for future human space missions.

As interest grows globally in establishing a human presence beyond Earth, including in orbit and on the Moon, understanding the health implications of long-duration space travel has become essential. Prolonged exposure to microgravity can lead to significant physiological changes in humans, such as bone density loss, muscle atrophy, and cardiovascular issues. Additionally, radiation exposure poses risks of genetic damage and increased cancer susceptibility.

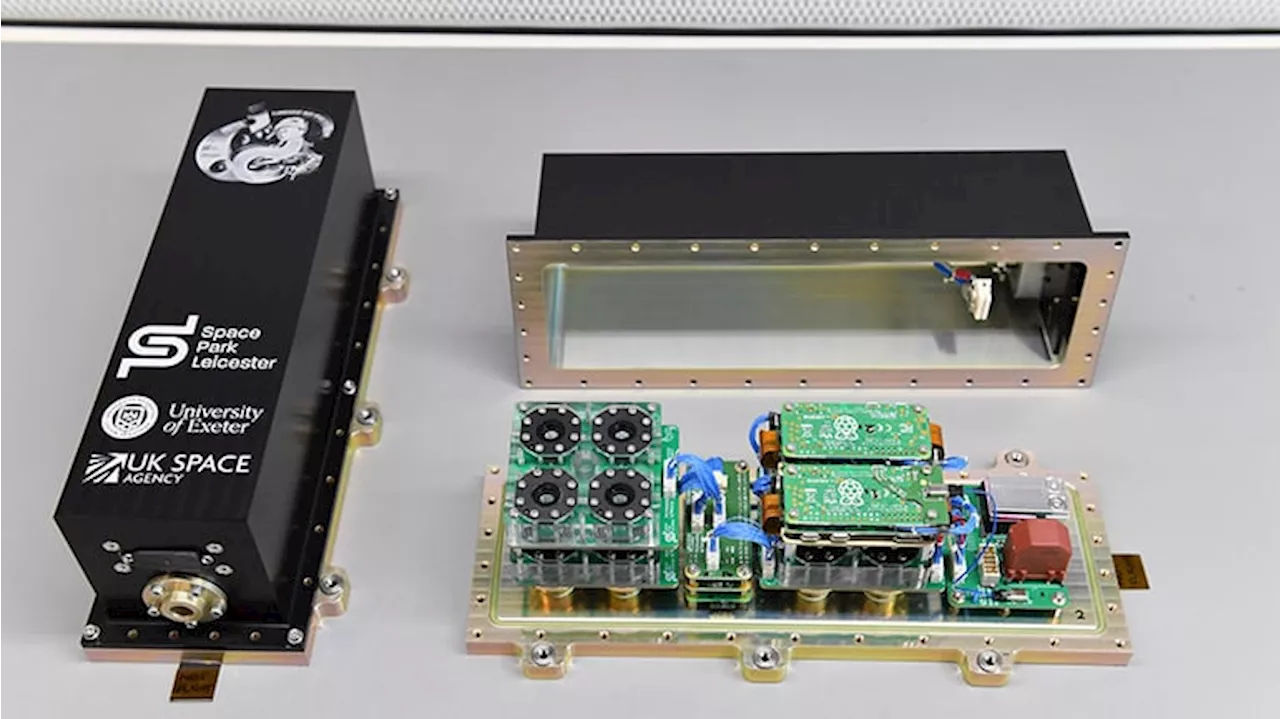

The FDSPP is designed as a self-contained unit measuring approximately 10x10x30 cm and weighing around 3 kg. It contains 12 Petri-Pods that provide a stable atmosphere and nutrients for the organisms while being exposed to the vacuum of space. Notably, the experiment will involve C. elegans nematode worms, which will be monitored using natural fluorescent markers installed prior to launch.

Professor Mark Sims, project manager for the FDSPP at the University of Leicester, emphasized the significance of this mission. “This mission to the International Space Station will demonstrate the flight readiness of FDSPP. Its success will help position the UK among global leaders in life sciences research,” he stated. The FDSPP is scheduled for launch as part of a cargo flight to the International Space Station (ISS) in April 2026.

Once onboard the ISS, the worms will be housed in four of the Petri-Pods, with the remaining eight dedicated to other microorganisms and test subjects. After a brief period inside the station, the unit will be deployed outside for 15 weeks to expose it to the harsh conditions of space, including radiation and microgravity. During this time, the unit will collect vital data regarding temperature, pressure, and radiation levels, relaying this information via the ISS downlink system.

Professor Tim Etheridge, principal investigator from the University of Exeter, highlighted the importance of conducting biological research in space. “This hardware, made possible through strong collaboration between biologists and engineers, will offer scientists a new way to understand and prevent health changes in deep space,” he noted.

The research is crucial for developing strategies and medical treatments to mitigate the long-term effects of space travel. While exercise regimens are essential for astronauts to combat muscle and bone loss, further medical interventions will be necessary to address impacts on organ function and mental health.

This experiment aims to answer a pivotal question in space exploration: Can living organisms, including humans, safely develop and thrive in space or on other celestial bodies? The implications of this research extend beyond immediate health concerns, potentially influencing future missions and the possibility of human habitation beyond Earth. As the field of space biology progresses, the findings from the FDSPP could play a significant role in shaping our understanding of life in the cosmos.