West Virginia is experiencing a significant shift as data centers and bitcoin mines emerge as new economic players, reminiscent of the coal industry’s past. This transformation is not merely an economic trend but a change that could impact local communities profoundly, seen through rising utility bills, depleting water resources, and altered landscapes. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, at least 37 states have revised tax codes and regulations to attract data centers, granting billions in exemptions annually. In West Virginia, this trend is particularly pronounced, reflecting patterns established during the coal boom.

The current data center boom has raised concerns about environmental and social consequences. Industry representatives tout the benefits of these facilities, often highlighting the promise of jobs and technological advancement. For instance, Blockchain Power Corp. has positioned itself as a pioneer in the state, establishing five bitcoin mines on former coal sites in Hazelton, Ben’s Run, Tunnelton, Miracle Run, and Blacksville. These facilities require approximately 107 megawatts of power to operate, utilizing vast amounts of water—up to several million gallons daily—equivalent to the needs of towns with populations ranging from 10,000 to 50,000 people.

Local residents are now grappling with the implications of this industrial shift. Unlike the coal industry, which at least provided hundreds of jobs, data centers employ a fraction of that workforce. For example, Blockchain Power Corp.’s operations employ only 44 people, raising questions about the economic trade-offs involved in the transition. The perception of these facilities is often shrouded in marketing lingo, with executives discussing “work ethic” and proclaiming the area’s “abundant water” resources.

Regulatory Changes Favor Corporations

Recent legislation, including the Power Generation and Consumption Act signed by Republican Governor Patrick Morrisey in April, has facilitated the entry of these data centers. The Act creates a favorable environment for corporations, allowing them to bypass local regulations around zoning, noise, and land use. County governments receive only 30% of the tax revenue, with the state retaining the remainder, further diminishing local authority.

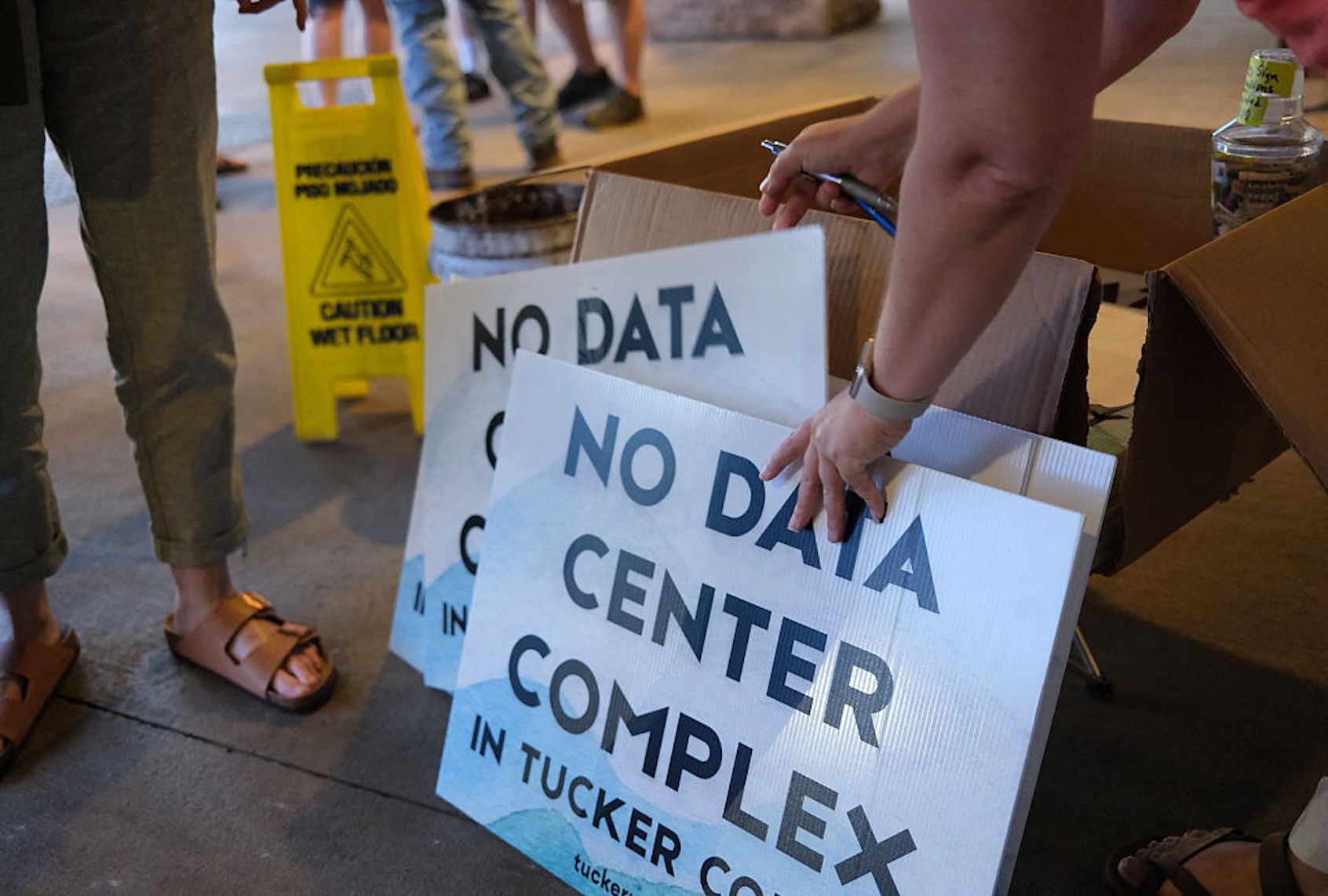

In Tucker County, plans for an off-grid gas plant between the towns of Thomas and Davis have sparked community concern. Residents are seeking clarity on critical issues such as water sourcing, noise levels, and long-term job prospects but are often met with vague responses and redacted permit documents. As the state continues to promote itself as “open for business,” many locals feel sidelined, left to navigate the ramifications of decisions made behind closed doors.

The situation is not unique to Tucker County. Mingo County is considering additional off-grid plants, while Jefferson and Berkeley counties have similar projects in development. Harvard University’s research highlights a crucial point: as industrial customers demand more power, the burden frequently shifts to residential consumers, resulting in higher utility costs.

Lessons from the Past

West Virginians are acutely aware of the cycles of economic promise and subsequent disillusionment. Historical patterns show how the coal industry’s promises of prosperity often gave way to environmental degradation and economic displacement. The current data center industry appears to repeat this narrative, with the potential for significant local disruption while the benefits largely flow elsewhere.

The short-term nature of the data center industry raises further concerns. Many of these facilities may not remain viable in the long run as market demands fluctuate. The volatile nature of bitcoin and artificial intelligence workloads could lead to sudden exits, leaving behind infrastructure that communities must maintain without the promised economic support.

As residents reflect on past experiences, they remain cautious of new developments. The challenges they face now echo historical grievances related to coal mining, including infrastructure damage and environmental contamination. The lessons learned from previous industries weigh heavily on current discussions, as the community assesses whether the new wave of data centers will bring lasting benefits or simply replicate the outdated patterns of extraction that have long plagued West Virginia.

In conclusion, as West Virginia navigates this new landscape shaped by data centers, it is essential for policymakers and community members to engage in transparent discussions about the balance between economic development and the protection of local resources. The stakes are high, and the outcomes will resonate for generations to come.